Guide to direct action for workers

This translation was adapted by our comrades in the Brussels branch from a pamphlet published by BossBusters, a Bay Area IWW project (San Francisco).

Direct action is any form of activity that cripples the boss's ability to make a profit and forces him to give in to workers' demands.. The best known form of direct action is the strike., in which workers simply quit their jobs and refuse to produce profits for the boss until they get what they want. This is the preferred tactic of the “traditional unions”, but it's actually not necessarily the best way to oppose the boss.

The indignity of working to survive is well known to all who have done it. Democracy, the great principle upon which our society is supposed to be founded, is thrown out the window as soon as you show up on time for work. As we have no control over what we produce, nor on the way in which this production is organized, and that only a small portion of the value of that product ends up on our paycheck, we have the right to resent our bosses.

Ultimately, of course, we need to create a society in which workers make all the decisions about the production and distribution of goods and services. Harmful or unnecessary industries, like making weapons, or bank and insurance scams, would be eliminated. Basic necessities, like food, housing and clothing, could be produced by anyone working just a few hours a week.

Waiting, however, we must develop strategies that foreshadow this future AND that counteract the daily drudgery of contemporary wage bondage. Direct action in the workplace is the key to achieving both goals. But what do we mean by direct action? ?

bosses, with their large financial reserves, are better able to withstand a long-term strike than the workers. In many cases, court injunctions will freeze or confiscate union strike funds. And the worst, it's that a long walkout only gives the boss a chance to replace striking workers with replacement labor.

Workers are much more effective when they take direct action while staying in the workplace. By deliberately reducing the boss's profits while continuing to collect wages, you can cripple the boss without giving a scab a chance to take your place. Direct action, by definition, designates tactics that workers can undertake on their own, without the help of government agencies, union bureaucrats or expensive lawyers. Seeking help from government or legal agencies may be appropriate in some cases, but it is NOT a form of direct action.

Here are some of the most popular forms of direct action workers used to get what they wanted. However, almost every one of these tactics is, technically speaking, illegal. All of the great victories that unions have won over the years have been achieved through militant direct action that was, at the time, illegal and subject to police repression. After all, until the beginning of the 20th century, union laws were simple – there were none. Most Courts Viewed Unions as Illegal Conspiracies to Obstruct 'Free Trade', and the strikers were regularly attacked by the police, private security troops and henchmen.

The legal right of workers to organize is now officially recognized, but there are so many restrictions that effective action is more difficult than ever. This is why any worker considering direct action in the workplace – bypassing the legal system and hitting the boss where he is weakest – must be fully aware of labor law., its application and how it can be used against militant workers. At the same time, workers must realize that the struggle between bosses and workers is not a badminton match – it is war. In these circumstances, workers should use what works, whether the bosses like it or not (and their courts).

Here are the most useful forms of direct action :

Slow-down

Slowdown has a long and honorable history. In 1899, Glasgow's organized dockworkers demanded an increase in 10 % salaries, but met with the refusal of the bosses and went on strike. Strikebreakers were recruited among agricultural workers, and the dockers had to concede defeat and return to work with the old wages. But before going back to work, they heard this from their union secretary :

“You will return to work at the old salary. The employers kept repeating that they were delighted with the work of the farm workers who took our place during several weeks of strike. But we saw them at work. We saw that they couldn't even walk on a ship and they dropped half the goods they were carrying ; short, that two of them could barely do the job of one of us. However, the bosses declared themselves delighted with the work of these fellows. well, there is nothing else for us to do but the same. Work as farm laborers have worked. »

This order was obeyed to the letter. After a few days, the contractors summoned the secretary of the union and begged him to tell the dockers to work as before, and that they were ready to grant the salary increase of 10%.

At the beginning of the century, a gang of workers working on a railroad in Indiana, in the USA, was informed of a pay cut. The workers immediately brought their shovels to the blacksmith shop and cut two centimeters on the shovels. Returning to work, they told the boss "reduced salary, reduced shovels ».

From work to rule (Work to rule)

Almost every job is covered by a maze of rules, regulations, standing orders, etc., many of which are completely inapplicable and generally ignored. Workers often violate orders, use their own techniques to get things done and ignore lines of authority just to achieve business goals. It is often tacitly accepted, even by managers whose job it is to enforce the rules, that these shortcuts must be taken in order to meet production quotas on time.

But what if each of these rules were followed to the letter? ? This would result in confusion, a drop in production and morale. And especially, workers can't get in trouble with this tactic because, after all, they just "follow the rules".

under nationalization, French railway strikes were banned. However, railway workers have found other ways to air their grievances. A French law obliges the engineer to ensure the safety of any bridge over which the train must pass. And, after a personal examination, he still has doubts, he must consult the other members of the train crew. Of course, all the bridges were thus inspected, all the teams were thus consulted, and none of the trains ran on time.

In order to obtain certain demands without losing their jobs, Austrian postal workers have strictly observed the rule that all mail must be weighed to check whether the correct postage is applied. previously, they passed without weighing all the letters and all the parcels whose weight was obviously insufficient, thus respecting the spirit of the regulation but not its exact wording. By bringing each piece of mail to the scale, weighing it carefully, then putting it back in its place, the postal workers kept the office cluttered with unweighed mail on the second day.

The Good Work Strike

One of the biggest problems for workers in the service sector is that many forms of direct action, such as slowdowns, end up harming the consumer (mainly work colleagues) more than the boss. One way around this problem is to provide better or cheaper service – at the patron's expense., of course.

Workers at Mercy Hospital in France, who feared that patients would not be treated if they went on strike, refused to complete drug billing slips, laboratory tests, treatments and therapies. Consequently, patients received better care (since they spent their time taking care of them instead of filling out paperwork), and this for free. Hospital revenues have been cut in half and administrators, panicked, gave in to all the demands of the workers after three days.

In 1968, Lisbon bus and train workers offered free rides to all passengers in protest at the refusal to raise wages. Train conductors and conductors arrived at work as usual, but the conductors did not take their bag of money. Needless to say, public support was firmly entrenched in the camp of these strikers.

At New York, IWW catering workers, after losing a strike, got some of their demands by following the advice of IWW organizers : « stack the plates, serve them twice and calculate the checks [bills] at the lowest ".

Sitting strike

An attack does not need to be long to be effective. Well planned and executed, a strike can be won in minutes. These are “sitting” strikes, when everyone stops work and stays seated, or mass strikes, when everyone leaves work to go to the boss's office to discuss an important matter.

The Detroit IWW used the sitdown (sitting strike) wisely to the Hudson Motor Car Company between 1932 and 1934. The message 'Sit back and watch your pay rise' circulated along the assembly line on stickers affixed to work tools. The regular practice of the sit-down strike has made it possible to increase the wages of 100 % (from 0,75 dollar per hour 1,50 dollar) in full depression.

Theatrical extras of the IWW, facing a pay cut of 50 %, waited for the right moment to strike. For the play, 150 extras were dressed as Roman soldiers to carry the queen on stage. When the signal for the queen's entry has been given, the extras surrounded her and refused to move until the salary was not only reinstated, but tripled.

Sitting occupations are always powerful weapons. In 1980, the KKR Corporation has announced that it will close its factory in Houdaille, in Ontario, and move her to South Carolina. The workers responded by occupying the factory for two weeks. KKR was forced to negotiate fair terms for plant closure, including full board, severance pay and payment of health insurance premiums.

Selective strikes

Unpredictability is a great weapon in the hands of workers. Pennsylvania teachers used the selective strike to good effect by 1991, when they picketed on Monday and Tuesday, reported to work on Wednesday, struck again on Thursday and reported to work on Friday and Monday.

This alternating tactic not only prevented administrators from hiring scabs to replace teachers, but also forced administrators who had not set foot in a classroom in years to work in schools while teachers were away. This tactic was so effective that the Pennsylvania legislature quickly introduced bills to outlaw selective strikes..

Alert launcher

Sometimes, just telling the truth about what's going on at work can put a lot of pressure on the boss. Consumer industries like restaurants and packaging plants are the most vulnerable. And once again, as in the case of the good work strike, you will gain public support, whose support can make or break a business.

Whistleblowing can be as simple as a one-on-one conversation with a client, or as dramatic as the engineer of P.G.&E. which revealed that the plans for Diablo Canyon's nuclear reactor had been reversed. Le roman d’Upton Sinclair, the jungle, exposed the health standards and outrageous working conditions of the meatpacking industry when it was published at the turn of the century.

Servers can explain to their customers the various shortcuts and substitutions that go into making up the fake haute cuisine served to them. Just as Rule work puts an end to the usual loosening of standards, the technique of whistleblowers brings it to light

Sick-In

The Sick-In is a good way to strike without striking. The idea is to cripple your workplace by having almost all workers call in sick on the same day or days.. Unlike the official walkout, it can be used effectively by single departments and work areas, and can often be used successfully even without formal union organization. This is the traditional method of direct action for public sector employee unions, who are legally prevented from striking (because of the minimum service in the USA).

In a mental hospital in New England, the mere idea of a Sick-In yielded results. A union representative, talking to a supervisor about a fired union member, casually mentioned that there was a lot of flu in the air and that it would be a shame if there were not enough healthy people to fill the services. At the same time – by pure coincidence, of course – dozens of people were calling the personnel office to find out how many sick days they had left. The supervisor understood the message and the trade unionist was rehired.

dual power (Ignore the boss)

The best way to get something is to organize and do it yourself. Rather than waiting for the boss to give in to our demands and institute the long-awaited changes, we often have the power to effect these changes on our own, without the boss's approval.

The owner of a San Francisco cafe mismanaged his money and, one week, salary checks did not arrive. The manager continued to assure the workers that the checks would arrive soon, but the workers eventually took matters into their own hands. They started to pay each other day by day directly in the cash register, leaving receipts for amounts advanced so that everything is in order. This caused an uproar, but the checks then always arrived on time.

In a small print shop in San Francisco's financial district, an old, dilapidated offset press was finally taken out of service and pushed into the back of the press room. It was replaced with a brand new machine, and the director declared his intention to use the old press “only for envelopes”. But the operators started cannibalizing her for spare parts., in order to operate the other presses. Very quickly, it became obvious to everyone, except for the director, that this press would never be used again.

The printers asked the manager to move her upstairs, in the storage room, because it was just taking up valuable space in an already overcrowded press room. He procrastinated and never seemed to want to deal with it. Finally, an afternoon, after the printers have clocked in for the day, they took a moving cart and pushed the press into the elevator to take her upstairs. The manager found them just as they put her in the elevator, and though he grew enraged at this blatant usurpation of his authority, he never told them about the incident. The space where the press was located has been transformed into an “employee lounge”, with several chairs and a magazine rack.

Monkey-Wrenching

“Monkey-wrenching” is the generic term for a whole series of tricks, devilishness and various nastiness that can remind the boss how much he needs his employees (and how little they need him). If all these control tactics are non-violent, most of them constitute major social taboos. They should only be used in the fiercest battles, when it comes to open warfare between workers and bosses.

The disruption of magnetically stored information (like the tapes, Floppy disks and poorly protected hard drives) can be achieved by exposing them to a strong magnetic field. Of course, it would be just as easy to "misplace" discs and tapes that contain this vital information. Restaurant workers can buy a bunch of live crickets or mice from the neighborhood pet store, and release them in a suitable place. To laugh better, give an anonymous call to the Health and Safety Executive (health control agency).

One thing that always haunts a strike call is the issue of scabs.. During a railway strike in 1886, the scab problem was solved by strikers taking home “souvenirs” from work. Curiously, trains couldn't run without these essential little parts, and the scabs were left with nothing to do. Of course, of our time, it may be safer for workers to simply hide these parts in a safe place in the workplace, rather than trying to smuggle them out of the factory.

Use the boss's header to order a ton of unwanted office supplies and have them delivered to the office. If your company has a number 800 (green/free number), ask all your friends to block the phone lines with angry calls about the current situation. Get creative with the use of superglue. the possibilities are limitless.

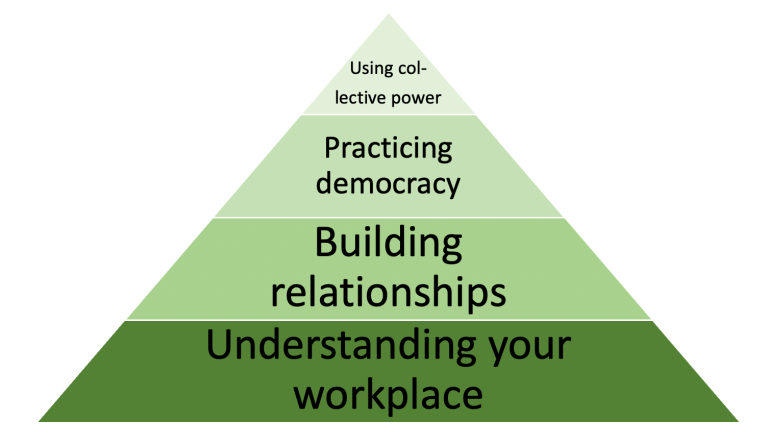

Solidarity

The best weapon is, of course, the organization. If a worker stands up and protests, the bosses will crush him like an insect. Crushed bugs are obviously of little use to their families, their friends and social movements in general. But if all the workers get up together, the boss will have no choice but to take you seriously. It can dismiss any individual worker who makes agitation, but it may struggle to lay off its entire workforce.

The success of all the tactics discussed here depends on solidarity, coordinated actions of a large number of workers. Individual acts of sabotage offer little more than a fleeting sense of revenge, what, it is true, may be the only thing keeping you sane on a bad day at work. But for a real sense of collective emancipation, nothing beats direct action by large numbers of disgruntled workers.